“Let’s go around the circle and—”

Never have five words instilled such dread in me. I have memories of myself back in a kindergarten classroom, standing in a circle while my classmates introduced themselves. When it was their turn, they told the class their favorite color or what they did over the summer. Some were enthusiastic, others shy.

None of them were me.

I had no voice at all. I was powerless as I waited for what was (in my mind) the Circle of Doom to land on me. I didn’t know the kids to my left and right, and I couldn’t ask anyone to skip me, so the teacher didn’t. “Tell us something about you,” she said. I opened my mouth, but no words came out. The teacher gave a strained smile and repeated the question, thinking I didn’t hear her. I heard her—I knew I was supposed to answer the question, yet all I could do was freeze and wait for her to get the message.

It took many moments for the teacher to realize I wouldn’t answer. Dozens of six-year-old eyes stared me down, all because the reply that my favorite color was light pink was stuck in my throat. It wasn’t that I wouldn’t speak, as everyone assumed. It wasn’t that I was stubborn and chose silent treatment to get my way. I simply couldn’t. My vocal cords, normally fine, stopped functioning as soon as my mom dropped me off at my elementary school door. I’d say goodbye to her, but I could only wave if anyone else tried to greet me. It was one of the worst feelings imaginable, especially since I was only a child and didn’t understand why all the responses clashing in my head dumbed down to silence. I knew what I looked like, body frozen and face entirely blank. I needed help, but I couldn’t show it using my body language or my voice.

Later that year, I got diagnosed with selective mutism disorder, a severe anxiety disorder most common in children. I had a label for that awful catatonia. I don’t remember the formal screening process—I was too young—but I’ll always be grateful to my parents for noticing my struggle and doing something about it. Although they must’ve been confused and agitated about me “acting oddly”, they took me to a behavioral therapist to get evaluated. If they hadn’t, I might’ve kept burrowing into my shell forever.

I’ve since thought a lot about what could’ve caused my mutism. I remember, vaguely, lying on a carpet in preschool and contemplating what it would be like to not talk, then experimenting by doing just that. That was the starting point of it all. Honestly, I can’t pretend I’m not sometimes furious at my younger self for forcing me into a whole incredibly frustrating mental health journey just because she was curious about what would happen. It’s even worse since that moment fractured my life into two chapters: Before Selective Mutism and After Selective Mutism. I spoke with no problem before that.

My anxiety manifested in other ways as well, not just becoming unresponsive and freezing up. For the first two years of elementary school, around kindergarten to late first grade or early second grade, I couldn’t eat in school or ask to use the bathroom. Teachers tried to help me, letting me use the bathroom in the nurse’s office or eat in a space other than the cafeteria. It didn’t work. I couldn’t shake the feeling these adults (who were only trying to accommodate me) would judge me if I did eat or use the restroom, like me finally “giving in” would warrant some huge, uncomfortable reaction. That phrase “I couldn’t” seemed to trail me everywhere.

What I was most afraid of was other people having strong reactions if I finally talked. I worried about people being shocked, gasping out loud, or pointing at me. I feared drawing attention. I hated when people made a big deal of me, so as a first grader, I preferred to stay off to the side and become unnoticeable rather than make an effort to fit in and face the consequences. If I knew for sure nobody would care if I suddenly broke my silence, I would’ve done it much sooner.

I wasn’t scared they’d judge my voice but the fact that I talked at all. As I stayed silent, my peers formed this image of me as the quiet girl. I was artistic and academically smart, sure, but silent, which is generally a deficit when trying to socialize with others. However, I did make friends. I’ve never been without friends—these friends accepted that I didn’t talk and played with me at recess or came over to my house anyway. They were good to me, as good as little kids could be, and I appreciated that a lot. Still, the disorder worked against me. As the days ticked by, it became harder for me to even consider breaking out of my quietness. I’d gone so long silent that it wasn’t even worth it at this point to try to change it, right?

I had friends, which helped, but they couldn’t rewire my brain. Too anxious to eat around my peers, I starved each day from 8 to 3. I couldn’t even eat the snack my mom packed for me during snack time because, again, I was scared someone would comment on it. My abstinence became a pattern; patterns became a resistance to change. At the end of the school day, as we drove past the school in my babysitter’s car, I would finally eat all of my lunch. Where nobody could see me. It wasn’t an eating disorder, just an extension of my anxiety. My mom tried to pack fruit smoothies for me in place of lunch since they were a drink and not food (I could drink water during school without issue) but I’d drink a few sips and then stop.

No matter how much I tried to, I obviously couldn’t avoid my classmates entirely. I had so much trouble communicating with others because they’d always misunderstand me. I could only nod and shake my head at them, and they hadn’t learned to somewhat interpret my hand signals the way my friends had. It was like a language barrier. In a way, I guess it was. I know it wasn’t their fault, but I was known as Other to them. I was different, strange, odd.

My diagnosis meant I could get a 504 plan, a document that listed accommodations I had for my selective mutism. My teachers referred to it to help me, so they knew not to call on me randomly or try to force me to speak. They let me skip my verbal reading assessments and gave me white boards and notepads to write with so I could feel included in class discussions. They were doing the best they could. They were doing all they could, but I think I’ve always had a strong aversion to “extra help”, even if I genuinely need it. My young self found it demeaning. I absolutely loathed going around the circle and, instead of being skipped, giving an answer scrawled on a white board. The few seconds of shifting, awkward eyes while I wrote my Expo marker response always got to me. I felt like an animal.

In first grade came that event that shook me to my bones. For their birthday celebration, everyone eventually had to bring a parent in to read their favorite picture book aloud. My dad came on December 11th, and the reading went fine. That is, until he pulled out his phone and played a video.

The video was of me sitting in my dad’s office in teal pajamas and talking to him in this playful, high-pitched voice. I was only comfortable speaking around my family—I sat in his nook overlooking the window and just talked. He recorded me, and I assumed it was to save the memory. After he recorded, I specifically asked him not to show the recording to other people. He promised he wouldn’t.

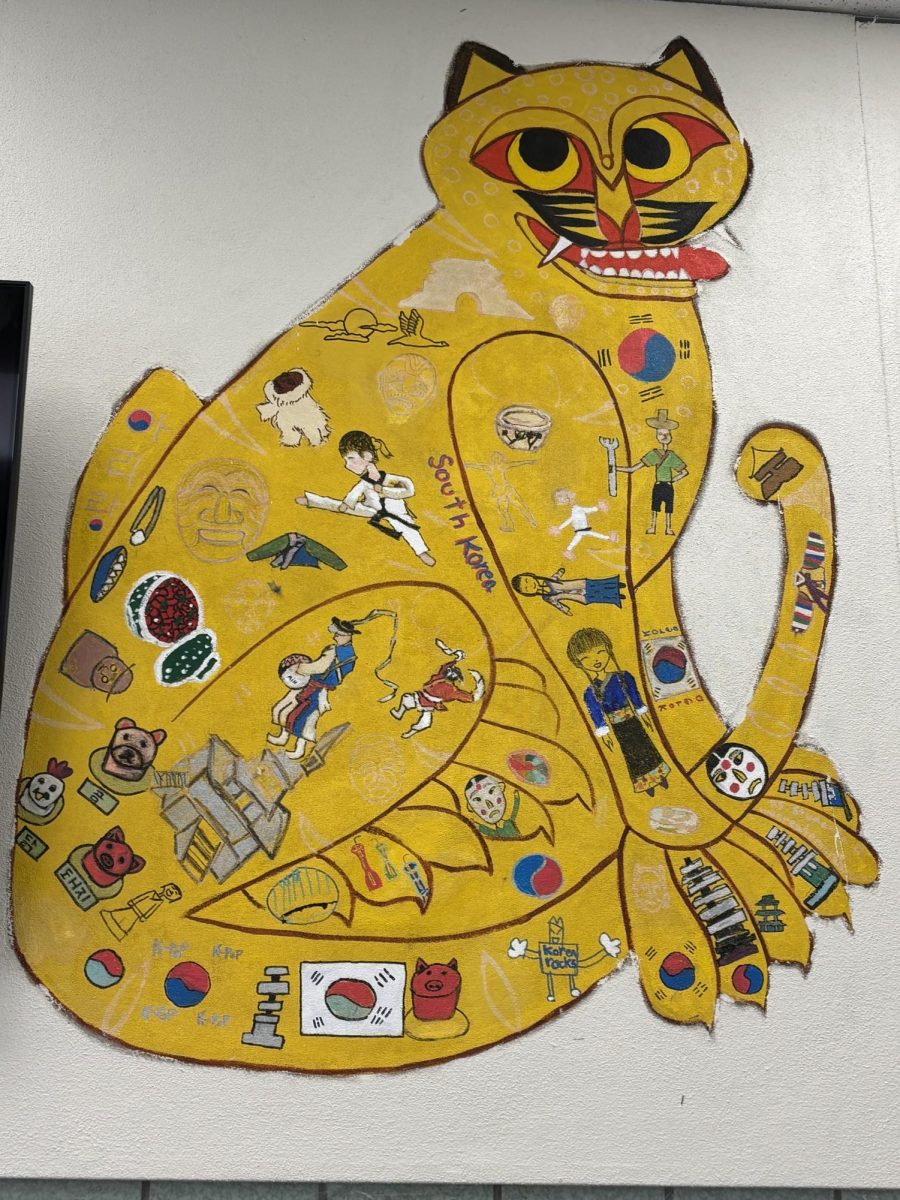

Do you know what he did? He showed that video to my entire first grade class. It was a private, silly video of me he swore he wouldn’t share with anyone. He was so quick to break what I thought was a promise. It broke me. I know he was trying to help me open up in the only way he knew how to, trying to lift me up and move me forward. It did the absolute opposite. It just made me less inclined to talk.I still look back on it as one of my most embarrassing moments, and it felt in the moment like the deepest cut of betrayal. Young me was ready to never forgive him for it. I came up with this: my own dad, my 아빠, didn’t understand my SM. He went against what he said he’d do, and that hurt. A lot.

In second grade, my parents got me books about real people with selective mutism. It was so cathartic to realize I wasn’t all alone, that just because I was the only selectively mute kid in my grade didn’t mean I was the only one in the world. The downside was all the authors overcame it earlier, just months after they were diagnosed. I felt alienated for having gone through for two years with no discernible progress.

After that, I did make some progress. It finally became a steep upward slope instead of a plateau, and pretty much all of my major breakthroughs happened in second to fourth grade. I started eating in the cafeteria among my peers. I can only assume I took the goal in parts, eating in front of others only when my mom volunteered for lunch duty at school. I’m happy to say I don’t starve the whole school day anymore.

My mom helped me figure out what worked for me. I sent videos of me saying hi to people I wanted to start talking to in person. I did voice recordings and virtual reading assessments. It was easier to speak from behind a screen, although it still wasn’t easy. The first person I spoke to was a negative presence in my life—they threatened to end our friendship if I didn’t say one word to them within the next five seconds. I’m no longer friends with them today. The next person was easier and didn’t make a big deal of it, and my mom tells me it was like a dam broke when all the words I hadn’t been able to say to them came rushing out. Nobody quite had the shocked reaction I feared so much, which was a relief.

My circle expanded from there, but that isn’t to say my disorder magically cured itself. When I say nobody quite had such a visceral reaction to my talking, I mean they came close. The first person, the toxic friend (although I didn’t know it at the time) started screaming and running around when I told her I’d talked to the second person as well. It made my blood curdle.

I still didn’t raise my hand during class. As strange as it sounds, I found it easier to talk to strangers than to people who knew me. The strangers didn’t expect anything of me. They didn’t know I had selective mutism or expect me to be silent, so I could converse with them without them being shocked. Along those lines, I frequently wondered what it would’ve been like to move to a new town and a new school, where people didn’t know me for my mutism. I imagined being a whole different person, a girl who confidently raised her hand instead of suppressing her answers and keeping them in her head, a tangle of mental math and gymnastics.

It got better from there. There are still countless things about my journey that I haven’t mentioned here. I have a lot of things to say, which is why I’ve become a writer. I just want to remind you that just because someone is silent doesn’t mean they have no thoughts in their brain. They might not show their struggle in a way that’s easy to understand, but their struggle is still real. Just because someone has severe mental health issues and you don’t doesn’t make you stronger or them weaker. We are all going through something at some point. When my classmates realized I was speaking to some of my friends, some of them were bitter that I was “picking favorites”, which couldn’t be farther from the truth.

There’s not nearly enough mute representation in media. Society tramples all over the idea of muteness, automatically assuming that selectively mute people are just shy or socially awkward. It’s important to understand that shy, socially awkward, socially anxious, introverted, and selectively mute are all completely separate things, although they can coexist. Selective mutism is a disability; it impairs a person’s ability to talk and, sometimes, their ability to form lasting relationships. But disabled people are not unreachable. Bridge the gap between you and them if you can. If a teacher skips over someone during whole-class presentations, don’t immediately be outraged at their “special treatment”. If someone receives extra time for test-taking, don’t complain about it. Assume they have a 504 plan/IEP or just need different accommodations than you do to succeed the best they can in school. I hope after reading this, you will make an effort to be more understanding. I hope you will give people a little more grace.

Recovering from a mental health condition isn’t linear. There are days when I fall back on my 504 plan. I’m no longer in the clutches of selective mutism, although I still carry a lot of anxiety around. I took a Public Speaking elective this year because it was required, and I enjoyed it. I’m still not the first to raise my hand in a classroom—in fact, I try not to raise my hand if I can help it—but I’m no longer wound up like a string. I can talk to anyone now. However, I’m still naturally introverted, which isn’t a bad thing. In simple terms, it just means people are extremely tiring at times. Introversion isn’t a pathway to extroversion. You’d be surprised at how we introverts can thrive; I can’t help but cheer for my people.

My anxiety can still be debilitating. I still tell myself to stop “spinning my wheels” when it’s 4 a.m. and I’ve been through three consecutive sobbing breakdowns yet still can’t sleep. I’ve had multiple panic attacks and days where I’m so anxious it feels like I can do nothing but stalk around my room and wait for life to happen to me. This isn’t to say the recovery process is impossible or not worth it. You might be worried about not being taken seriously or that you won’t be able to explain what’s troubling you, but I’m sure there’s someone you trust. Start with that. To be vulnerable is not to be inferior.

My final note is to the ones with anxiety: I see you. I hear you. You’re valid. That’s all.